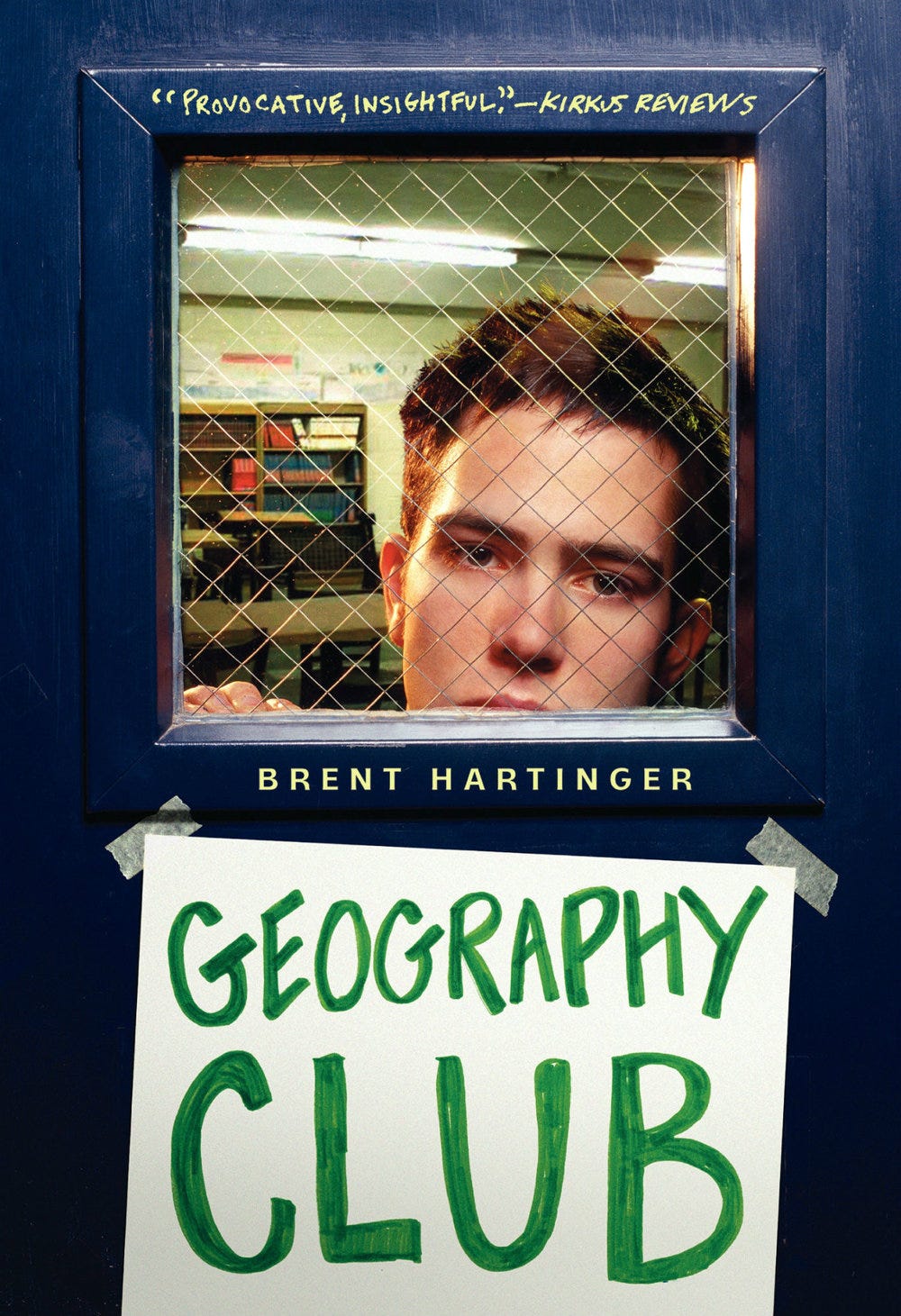

How Many Times was GEOGRAPHY CLUB Rejected Before it was Published?

It's complicated

A reader just asked me if minded telling how many publishers rejected Geography Club before it was finally published.

I don’t mind answering at all, but it’s a bit complicated, so when I give presentations, I usually just say, “38 publishers!”

Here’s the full story, which I’ve never before told in public, precisely because it is so complicated.

I wrote my first gay teen novel in 1989, right after college (I graduated young — I’m not THAT old!). The book was about a guy named Russel Middlebrook, who was a lot like Russel, and he had a best friend who was a lot like Gunnar. But there was no Min, no Kevin, and no Geography Club; the story was very different. It was about a closeted gay guy and his friendship with his gay swim coach. But it wasn’t a love story; it was a story of his coach being outed and the kid eventually coming to terms with being gay himself.

It was called Danny Britton’s Shadow. At one point, Russel’s coach tells a story about how he had always felt like he was in the shadow of the smartest, best kid in his class, Danny Britton. Until, of course, he learned that Danny Britten felt exactly the same way about him. In other words, the whole world lives in Danny Britton’s shadow, even Danny Britton! Everyone goes through life feeling like they’re not good enough.

All through the 1990s, I tried to sell this book to publishers.

Around 1995, the book won the SCBWI Judy Blume Grant for Unpublished Novels. I got a very nice note from Judy Blume herself, and the manuscript was requested by something like twenty-eight different editors. Three of them wanted to publish it and took it to the acquisitions departments at their publishing houses. But the accountants all said the same thing to those editors, “NO! There’s no market for a book about gay teens! You can’t publish it!”

I got increasingly frustrated/depressed, so much so that I eventually said, “To hell with it! I’m putting this aside and focusing on other books and my screenplays.” Around this time, I also moved to Hollywood where I had a couple of screenplays optioned and a play produced. (But none of the movies ever got made.)

Around 1998, I got a new agent, Jennifer DeChiara. She looked at all the stuff I’d written and said, “I like this Russel Middlebrook stuff best. I think I should pitch that.”

But I said, “Forget it! I’ve already tried everything. Everyone says the same thing: there’s no market for a book about gay teens.”

She said, “Trust me.”

I said, “Okay, but this manuscript isn’t as good as what I’m writing now. Plus, times have changed so much — I don’t think this book is as relevant as it used to be. Let me rewrite it.”

She said, “Just put together a proposal.”

I said, “I don’t need to write the whole book?”

She said, “No, just a proposal.”

So I wrote a book proposal for Geography Club: one chapter and a detailed outline. I did two things that I think were key to the book’s future success: (1) Danny Britton’s Shadowhad been really angst-y, but I tried to make Geography Clublighter and funny, and (2) I decided that it wasn’t going to be a story of self-discovery, it was going to be, in part, a love story. Even though he was closeted, Russel was going to know from the very beginning that he was gay and that he was totally okay with it. There would be absolutely no shame or self-hatred, because that already seemed very dated to me.

Geography Club literally started where Danny Britton’s Shadow had ended.

This proposal is what my agent took out to publishers. Thirty-eight of them eventually turned it down. But in early 2001, one editor, Steve Fraser at HarperCollins, made us an unusual offer: he said he would buy the proposal for a $5000 advance (and I’d then write the book on their dime), or I could wait and submit the whole book, and if they liked it, the advance would be $10,000.

Well, a bird in the hand is worth two in the bush, so I took the $5000. My agent, who always had complete confidence in this book, said, “You’ll make much more than that in royalties, so don’t worry.”

I was so worried that they were going to cancel the deal that I sat down and wrote the whole book in two and a half weeks. I’ve never written that fast before, or since. The day the contract was signed, I submitted the completed manuscript.

Steve had a few (good) suggestions, but this manuscript was very, very close to the book that ended up being published. It’s the least-edited book I’ve ever written. And, perhaps not surprisingly, this is probably also why there are a zillion things I now wish I could change. (Not really. Well, sorta.)

But please don’t think Steve wasn’t enormously helpful. He just gave me his best notes in the pre-contract, proposal stage, when we’d informally chatted about the book before it was even written. For example, in the original outline, Brian Bund commits suicide at the end of the book.

Steve said, “Please don’t do that. It’s way too serious, and it will change the book into something completely different.”

And he was so unbelievably right! Brian Bund’s suicide was a classic “deus ex machina” — a way to resolve my story that seemed profound, but was actually a total plot cheat. And tonally, it didn’t fit in there at all. I’d like to think I would have seen that on my own without Steve’s input, but I was pretty thick back then: I’m not sure I would have.

Incidentally, a side-note: the idea that an unpublished writer can submit a book proposal for a novel — especially a proposal that only includes ONE chapter! — and sell it to a major publisher is actually downright crazy. In fact, it may never have happened to anyone else in the entire history of publishing, before or since. But I’d won that award, and Steve and those other editors had read a couple of my other books, including Danny Britton’s Shadow. They knew I could write, and finish projects, so it wasn’t quite the risk that it maybe seems. And, of course, the subject matter was unusual back then — not a lot of people were writing gay teen novels because there was “no market,” remember? And the business of publishing was very, very different back then too.

The greater point is, there are rules in publishing, but there aren’t really any “rules.” Everyone’s path to publication is different (and oftentimes it’s downright crazy)

So anyway, the book was finished by May 2001, but then delayed a loooooong time. This really upset me at the time. And at the end of 2001, one of the editors at Simon & Schuster who had tried (and failed) to buy Danny Britton’s Shadow released Alex Sanchez’s Rainbow Boys. I loved the book, but I also thought, “Well, damn! That’s it, they’ve totally stolen my thunder!” Even I was thinking, “There can’t possibly be room for two gay teen novels in the world!”

I know, right? How stupid was I? (Sara Ryan also published a good lesbian-themed book around that time, Empress of the World. And I don’t mean to imply there weren’t other LGBT teen books before that, because there had definitely been a few, although most of them were long out of print.)

So anyway, about two years after the book was accepted (and almost fifteen years after I wrote the earliest draft), the book was finally published. It was March 4, 2003.

By the end of the second week, it had already gone into a third printing. It went on to sell … well, I’m not supposed to ever say exact sales figures, but many, many tens of thousands of copies.

The movie rights were almost immediately optioned (even though it would take another ten years before the movie actually got made). And I adapted the book into a stage play that’s been produced at least 15 times; I actually think the play is quite a bit better than the book, and I don’t think it’s ever not gotten a standing ovation. It often sells out too.

And my agent says that she heard from lots and lots of editors who said, “Why didn’t you send the book to me? I totally would have bought it!”

Uh huh, right.

As most of you know, I also turned the book into a four-book series, the Russel Middlebrook Series. And then I wrote another series about Russel in his twenties, Russel Middlebrook: the Futon Years. And then just this year I started a new series about one of Russel’s best friends, The Otto Digmore Series.

The moral of the story? I’m not sure there is one, except that gay teen novels, which are so popular now, were a really, really hard to sell in the 1990s.

And that when it comes to publishing, there are no rules and no one knows anything at all.