How Much Should an Artist Care About "the Market" — Or Even the Audience?

Writers who don't care at all annoy me almost as much as those who care too much.

Last month, the Washington Post chronicled a country music songwriter named Ashley Gorley who, as a kid, obsessed over what made some songs hits and others flops. He spent years studying pop music and eventually came up with a series of specific rules and formulas.

Now an artist himself, he’s written 83 number-one songs and is considered to be one of the most commercially successful songwriters of all time.

Meanwhile, you also have artists like Ari Aster and Jordan Peele — uncompromising filmmakers who questioned convention and didn’t concern themselves in the slightest with what the market or audience wanted.

As a result, they both broke new ground with their bold debut films: Hereditary and Get Out, respectively.

How much should an artist care about “the market” anyway? It’s literally one of the oldest questions in the arts: the conflict between art and commerce.

As artists, should we consider the audience at all — how they might receive the work in question, and whether the project might make us money? Or should we act entirely on artistic impulse, following our visions wherever they might lead, with no thought whatsoever to how the project will be received?

Conventional wisdom says there’s a spectrum: on one end, there is pure artistry, which is where all artists should try to be, because it’s where the best art always comes from.

At the other end of the spectrum is pure hackery, which we artists should fight at all costs, because the only thing that ever comes from this place is derivative or formulaic crap.

But honestly? I mostly reject this framing. The truth is, I think plenty of bad art has come even from a place of so-called artistic purity.

In fact, after their brilliant debut films, both Ari Aster and Jordan Peele were given carte blanche to make whatever movies they wanted.

And I think their subsequent films have been increasingly pretentious and self-indulgent — sometimes even virtually unwatchable.

Meanwhile, Ashley Gorley — that songwriter with all those hit records — clearly honed his craft before he even attempted a professional career, which is something I don’t think nearly enough artists do, and while I think some of his songs sound fairly generic, he sometimes shakes it up too. He’s actually considered one of the more innovative and groundbreaking songwriters working in Nashville today.

This is the way I’ve always approached my own art: existing in the tension somewhere between art and commerce — and I don’t think the “commerce” part of it is entirely bad.

One part of the artistic pursuit is, yes, self-expression. But another part is connection — communication with the audience. And if that’s your goal, it’s not insane to sometimes consider exactly what that connection might be.

In other words, I think it’s worth occasionally asking myself questions like: Will people understand this? Will anyone be interested in reading or watching it?

These questions aren’t that far from the question that every artist should always be asking: Is my vision fundamentally sound? Is this project “working”?

This isn’t to say that an artist should be open to these kinds of “market” and “audience” questions at every part of the artistic process. The truth is, when I’m in the middle of my first draft, I try hard to reside in that place of artistic purity, letting the needs of the story and the characters dictate exactly where the story is going, without regard for how the story might be received.

But I also don’t think it’s bad to set aside time to ask those “audience” and “market” questions too.

For me, that time comes in the “conceiving and outlining” stage, before I start writing the actual story. I think: Is this story worth writing?

Because, let’s face it, I write for a living, and my name isn’t “Christopher Nolan” — someone whose name alone will guarantee some kind of paycheck.

In other words, I don’t have the luxury of spending six months or a year working on a project that doesn’t sell — or even one that is an obvious “hard sell.”

And once I’m done writing the first draft of a project, I ask those oh-so-practical audience and marketing questions all over again.

But, yes, I’m also asking if my project is working — if my original confused mess of an idea is coalescing into something decent.

What does all this look like, practically speaking?

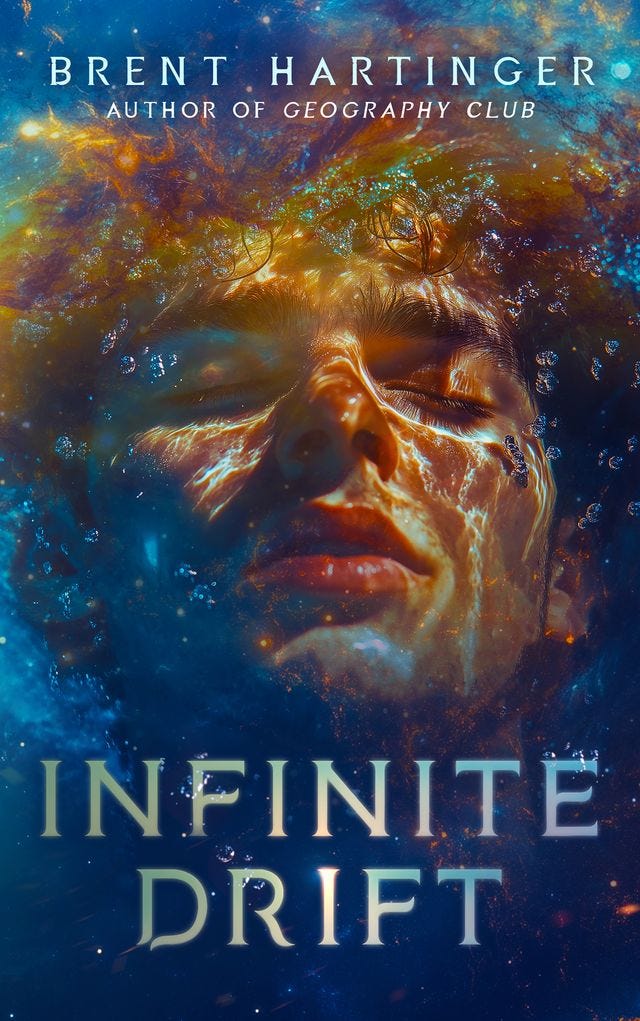

My latest novel, Infinite Drift — to be released in September 2025 — is the story of a teenager who, on a lark, gets into a “sensory deprivation” tank. But when he gets out again, the world is different in strange little ways. Later, when he tries the tank again, the world becomes even more different — and he has the strange feeling that someone is watching him.

Now he has to figure out what’s really going on. Has he crossed over into another dimension? Or is he going insane?

When I first came up with the idea, I had the same thought I always do: Do I really want to spend a year or so of my life writing this? Does the story seem like a worthwhile use of time?

But my next thoughts were about, yeah, the audience. Was there a market for this story? Did anyone else want a book like this?

I also thought about my author brand. I’m known for my books about gay teens — so maybe this character should be gay too?

Hold on, I thought. Since it’s a story about different dimensions and multiple possibilities, it might make more sense to make him bisexual. Yes! That epiphany made the story work much better, and in fact, it helped me clarify my theme.

But what about that aspect of multiple dimensions? Everything Everywhere All at Once hadn’t come out yet, and Star Trek and Marvel hadn’t gone full “multiverse” yet either, but there were still plenty of stories of alternative dimensions — there was clearly something in the air.

Now I thought, Hmmm. With all this talk of multiple dimensions, what if my story isn’t that exactly, but everyone thinks it is? How could I use that to play with the readers’ expectations?

Ultimately, of course, the artist’s process doesn’t matter. What matters is the resulting art — whether it’s any good or not.

But when it comes to books and movies that I read and watch, it seems like bad art results from the artist not seeming to care enough about the audience, as often as it does from the artist caring too much.

I think the place to be is the space between art and commerce.

In my case, it hasn’t meant dumbing my stories down or making them more formulaic.

No, I think it’s helped make them better.

P.S. Does Infinite Drift sound interesting? Check it out below:

GET THE BOOK AT BARNES AND NOBLE

(Are you a critic, podcaster, or book reviewer looking for an ARC? Go here.)

Brent Hartinger is a screenwriter and author. Check out his other newsletter about his travels at BrentAndMichaelAreGoingPlaces.com.

I research what books sell, but this hasn’t helped me to become more commercially successful. The idea of needing to reach a market can shut me down creatively. Thinking of an engaged audience, however, keeps me motivated. I love writing with a ideal reader in mind.

I really resonate with the balance you're striking here, Brent, between creativity and mindfulness of my readers. I think your premise is right on - to slavishly adhere to either side of that equation is not ideal. How to strike that balance is for each author to decide for themselves based on what their goals are. "Creativity vs market" is an example of one of the many things in life that, as leadership author Andy Stanley would say, is not a problem to be solved but a tension to be managed.