John Wasn't the "Cool" Beatle. Paul Was.

Last year, I visited Liverpool, and it reminded me of a really important lesson for all artists.

I learned about the Beatles in the spring of 1980 from my older brother, Craig. I was only a kid, but I started listening obsessively to their music and reading everything I could about the band.

But 1980 was a bad year to become a Beatles fan: John Lennon was murdered in December of that same year.

I’m still a massive fan — so much so that last year, my husband Michael and I went to Liverpool, England, to see the hometown of the band’s four famous members: Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison, and Richard Starkey (who is better known by his stage name, Ringo Starr).

There are lots of reasons why I love the Beatles, but it’s ultimately about their music. Almost every one of their 213+ songs includes some unique or interesting element — like those fantastic staccato violin chords in “Eleanor Rigby,” or the delightful lyrics to “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da” and how, at the end of the song, Desmond and Molly happily trade places, and she goes off to work in the marketplace, and he stays home with the kids — in 1968, about a decade before anyone had even heard the concept of a “stay-at-home husband.”

The Beatles are critical darlings — they’re widely considered the best and most influential force in popular music — but they’re also the best-selling musical act of all time, despite only producing music for eight years.

In other words, they’re one of the few artists in any medium who are arguably “the best ever” at what they did — and also the most popular.

They also illustrate some pretty profound truths about all artists — and all art. But to explain exactly what I mean by this, I have to express a somewhat controversial opinion:

John wasn’t the “cool” Beatle. Paul was.

John Lennon and Paul McCartney were the group’s primary songwriters, and they were both insanely creative but also intensely competitive. They agreed early on to share the songwriting credit on all Beatles songs, and initially, they wrote most of their songs together, each openly acknowledging that the other made him better.

As the years wore on, they still contributed to each other’s songs, but they primarily wrote alone — and their longstanding desire to upstage each other led to increasing musical greatness and sophistication on both sides.

Their artistic rivalry was so great that it arguably eventually even inspired the long-ignored George to start writing incredible songs. Interestingly, George’s delightful “Here Comes the Sun” is the most popular Beatles song on Spotify.

But John has long had the reputation as the “cool” Beatle.

That’s partly due to their demeanors. Paul was always the more optimistic, approachable, and non-threatening one — in real life and in his songs. And, in fairness, some of his post-Beatles work has been decidedly saccharine, which hasn’t helped his legacy.

John, meanwhile, was rebellious and edgy — the Beatle with “attitude.” In 1966, John caused an enormous controversy when he gave an interview where he said:

“Christianity will go. It will vanish and shrink. I needn’t argue about that; I’m right and I’ll be proved right. [The Beatles are] more popular than Jesus now; I don’t know which will go first: rock ‘n’ roll or Christianity. Jesus was all right but his disciples were thick and ordinary. It’s them twisting it that ruins it for me.”

Also in 1966, despite being married, John began dating an avant-garde artist named Yoko Ono. Soon, John was annoyingly insisting that Yoko sit in on all the Beatles’ formerly sacrosanct recording sessions. John and Yoko were also releasing their own “experimental” records, including a 1968 album of shrieks and strange noises recorded in one night with a photo of the two of them fully naked on the front cover.

In the Beatles, John tended to write harder-edged songs, like “Run for Your Life” and “Happiness is a Warm Gun.” In 1968, for the first single to be released on the Beatles’ new “Apple” record label, John — an open Marxist — pushed his song “Revolution”: a bold riff on radical political activism that even included a cheeky, approving nod to violent revolution.

It’s easy to see why so many people find John so interesting.

Meanwhile, while John was busy expressing himself — and pushing people’s buttons — Paul was more interested in “uncool” things like discipline, focus, and musical accessibility.

In fact, Ringo Starr himself recently specifically credited the Beatles’ success to Paul’s focus and discipline — his being a “workaholic.”

Back in 1968, Paul wanted one of his songs to be Apple’s first single, with a slightly sanitized version of John’s “Revolution” (disavowing violence) on the B-side.

Paul won the argument, and “Hey, Jude” broke sales records and quickly became known as one of the greatest songs of all time.

For John, self-expression — and, perhaps, provoking a reaction — was the most important thing. Paul was much more of a workhorse, more interested in melody, precision, and — oh, yes — innovation.

I’m glad John got off so many witty one-liners, and he definitely wrote some fantastic music, including three of my all-time favorite Beatles songs: “Girl,” “A Day in the Life,” and “The Ballad of John and Yoko.” He also wrote (with Yoko Ono) my single favorite ex-Beatles song, “Happy Xmas (War is Over).”

But while John was busy being sardonic, Paul was mastering virtually every music genre imaginable — from American country ( “Rocky Raccoon”), to boogie-woogie (“Lady Madonna”), to religious hymns (“Let it Be”), to doo-wop (“Oh! Darling”), to music hall (“Your Mother Should Know”), to romantic ballads (“Michelle” and “Here, There, and Everywhere”) — while also taking the time to write the most-covered song of all time (“Yesterday”) and also, arguably, create the world’s first heavy metal song (“Helter Skelter”).

That incredible eight-song medley on the flip side of Abbey Road? Paul’s idea — and mostly Paul’s songs.

And Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band — arguably the world’s first “concept” album and often considered possibly the greatest album of all time? Paul’s idea and, once again, mostly his work.

John was especially critical of what he called Paul’s “granny music” — namely, music that didn’t sound like typical rock ‘n roll.

But that criticism seems downright silly — and, I suspect, was the result of deep-seated jealousy — when you realize John meant timeless classics from Paul like “When I’m Sixty-Four,” “She’s Leaving Home,” "The Fool on the Hill,” “Mother Nature’s Son,” “Honey Pie,” and “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer.”

Paul sometimes criticized John’s music too. He didn’t like “Revolution 9,” the eight-minute experimental “sound collage” John did with Yoko for The Beatles album (also known as The White Album). John not only wanted to release the “song” as the album’s single, he also wanted it to be the future direction for all Beatles music.

But Paul was much less public with his criticisms. And he was also, well, right: “Revolution 9” is nonsensical and was a terrible direction for the Beatles — self-indulgent and lazy.

To be very clear, it was absolutely the tension and contrast between John and Paul that helped make the Beatles so incredible. John and Paul argued about the first single for Abbey Road too — and John correctly won that argument: “Come Together” over “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer” (on a double A-side single with George’s wonderful “Something”).

Even so, all this makes Paul sound pretty cool to me.

And my feelings about their respective “coolness” are only partly about the music. John could also be a real asshole — not just to the wife and child he abandoned in the 60s, but to his fellow bandmates.

The breakup of the Beatles was ugly, and John expressed his resentment of Paul in the lyrics of some of his solo work. In one song, “How Do You Sleep?”, he sings of Paul:

The only thing you done was yesterday

And since you're gone you're just another day

As usual with John, this is clever wordplay, referencing one of Paul’s most popular Beatles songs, “Yesterday,” and also a then-recent McCartney solo hit, “Another Day.”

But “uncool” Paul had the greatest mic-drop moment in the history of pop music when he responded to Lennon’s digs with his own song, “Silly Love Songs,” an infectious ditty that blithely dismissed John’s sour humorlessness and then joyously celebrated Paul’s own (inaccurate) reputation for writing only frothy songs without substance.

Some people want to fill the world with silly love songs

And what’s wrong with that, I’d like to know?

Cause here I go again

“Silly Love Songs” quickly became Paul’s 27th Billboard Hot 100 number one hit as a songwriter. His total now stands at 32 number ones — the all-time record.

And Lennon wasn’t just obnoxious to Paul. In one interview, he also said:

"Let’s say, I think it’s possible for John and Paul to have created [the Beatles] with two other guys. It may not have been possible for George and Ringo to have created it without John and Paul. OK?"

Which, frankly, is 100% true. But it’s also a 100% horrible thing to say about your former bandmates!

Truthfully, I know why the suggestion that John — not Paul — was the “cool” Beatle triggers me. It brings up two ideas about artists and the arts that I hate and that I profoundly disagree with:

That artistic genius is some romantic, involuntary state of being — not something that comes from discipline, focus, and years of plain old hard work.

And that artistic genius somehow excuses someone from being a total asshole.

John and Paul did have a reconciliation of sorts. In one of the last interviews before he was killed, John said about Paul:

“He's like a brother. I love him. Families — we certainly have our ups and downs and our quarrels. But at the end of the day, when it's all said and done, I would do anything for him, and I think he would do anything for me.”

And, of course, in “Here Today,” Paul’s stunningly beautiful musical tribute to John after he died, he sang about his former bandmate:

And if I say

I really loved you

And was glad you came along

Then you were here today

For you were in my song

When all was said and done, I think John, Paul, George, and Ringo all “came together” to understand that for the Beatles to become what they were, things had to go down exactly the way they did.

But I also think the personal characteristics of John and Paul — and the dynamic between them — really do illustrate some pretty interesting ideas about artists and art.

They force artists such as myself to ask ourselves some really great questions: What kind of artist do you want to be, and what kind of art are you trying to create? Is innovation more important to you — or is making a big splash? Is the artistic process mostly about inspiration — or is it more about dedication and hard work?

And maybe most importantly of all: as an artist, how are you going to treat other people? Is it more important to be hip and edgy and cool — or be a decent person?

Between John and Paul, I think Paul’s was the better approach.

In fact, the Beatles themselves put my personal sentiments rather nicely in the last lyrics in (almost) the last song on Abbey Road, the last album the Beatles recorded together:

And in the end, the love you take is equal to the love you make.

And yeah, Paul wrote that.

See also:

A Career in the Arts Isn’t a Normal Job. It’s More Like Being a Professional Athlete.

Madonna vs. Cyndi Lauper: What Their Careers Taught Me About Art

It’s Hard to Explain How Uncool It Used to Be to Be a Fantasy-Loving Dork

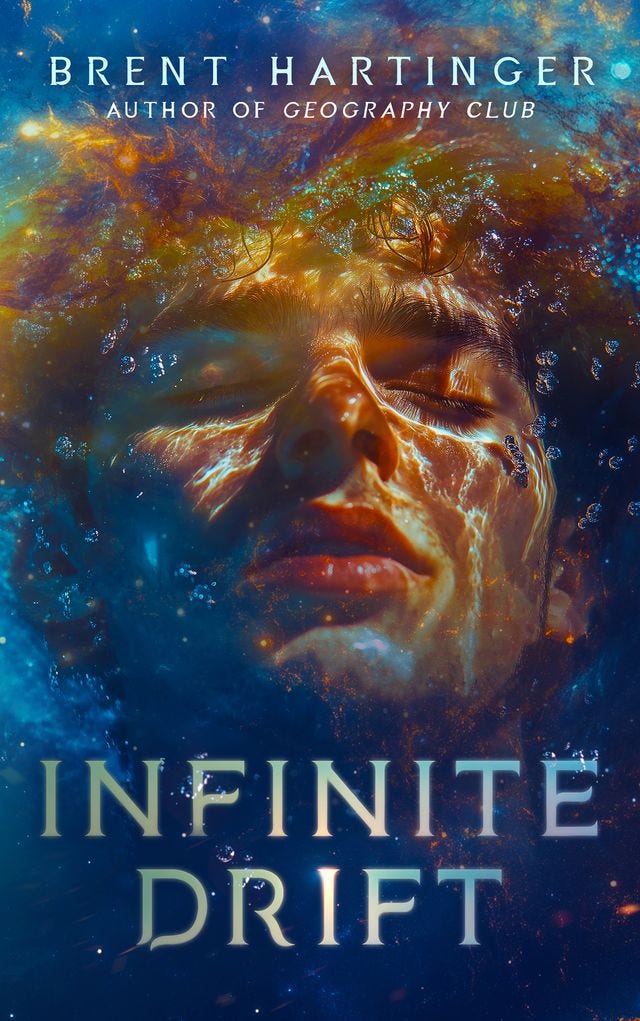

Brent Hartinger is a screenwriter and author. Check out my other newsletter about my travels at BrentAndMichaelAreGoingPlaces.com. And order my latest book, below.

I find the person that doesn’t want all the attention is often the most interesting

I learned to love the Beatles from my father who always favored Paul. When I asked about the coolness factor, he just shrugged. He couldn’t care less about the coolness factor (which I now find SO cool). “Paul is just the better song writer,” my father said.